Published on 12 December 2024

Generative AI has brought to the fore questions about assessment integrity – is the student doing what we asked them to do? (Reliability and validity are larger concepts (Dawson et al., 2024).)

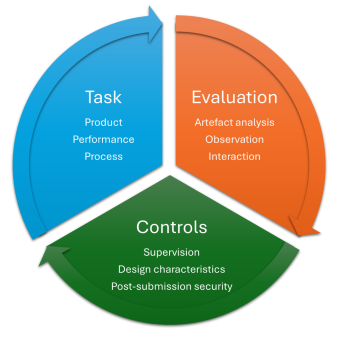

Integrity in assessment is a complex issue, but it can be simplified to a set of three components with three options in each. Like notes in a musical chord, all three concepts need to be considered together and the relationship between the options chosen affects the overall harmony.

The components and options are:

- three different types of tasks we set our students: production, performance and process;

- three ways we approach the evaluation of those tasks: (artefact) analysis, interaction and observation; and

- three ways we can increase the control of the assessment: design, supervision and post-submission security.

Each component is essential, and the interplay between them influences their effectiveness. It would be possible to have an assessment with all nine options, but usually there is only one evaluation method per task, while all three controls may often be present. [Click here for a diagram showing the interactions.]

Three types of tasks we set

Most assessments are one or a combination of three types of task: (artefact) production, performance and process. For assessments with multiple tasks we need to consider each separately. The overall integrity of the assessment is influenced by the weighting each task has in calculating the total grade.

Production is the creation of an artefact such as a document, material or device. Examples include exam scripts, reports, artwork, software code and electrical circuits. Some artefacts have a set form (such as multiple-choice answers selected); others require a creative process. However, the assessment brief may not require or evaluate that process – if so, students can only be evaluated on the submitted product. Often production is unsupervised, and if process is evaluated, it is often via the proxy of a written report – itself a product. Products (artefacts) can only be evaluated by analysis.

Performance describes all those activities where a student does something to demonstrate learning. It includes actions such as presentations, class discussion, chemical titration or landing an aeroplane. The performance itself is ephemeral – any recording of performance leads to another category, the production of an artefact. Because it is ephemeral it can only be evaluated by observation. There is no assessment of the preparation for a performance, or associated documents. If a presentation has an assessed slide deck, that is a product separate from the performance.

Process is arguably the most important assessment requirement, as it captures the way in which the student learns and applies their learning to the assessment task. (cf Fawns, 2024) Process captures all those activities and thinking that go into research, creativity, drafting and development of artefacts and performances. Thus, there is no production or performance without prior process. But as process is so close to learning, it can be hard to evaluate.

Many tasks sit on the boundaries or include two components – so this division is heuristic. This can be helpful. Although the creation of a bibliography is process-heavy, if we award marks to the final structure of it, we are assessing it as a product. A discussion in class might be both a student’s thinking process and also a performance if the class is listening. Considering how it feels to the student can help us to reconsider how best to assess the task.

Three evaluations methods

We assess through an external lens on the student’s activity. Often we only assess part of the student’s work.

Artefact analysis is when we assess what a student has produced. This can take place at any time after the creation of the artefact, so long as the artefact still exists. This is a passive evaluation, remote in time and place; the evaluator only has the student’s artefact to view. Essays, reports and exam scripts are common forms, but artefacts also include audiovisual materials, physical and mixed-media products and documentation of research or processes undertaken. Even though such documentation describes a process, as artefacts they are subject to the same integrity issues as any other artefact. Artefact evaluation is always separated in time and place from the student’s work – there is no natural supervision of the student. This has to be overcome by control measures.

Observations are when we evaluate through watching a student’s behaviour – either undertaking a process or performing. The evaluator is passive in this process, and unable to see beyond the performance itself – any conclusions about preparation or approach are implications. As with interactions, observation is always a supervised assessment, but it also evaluates the student as well as controlling the environment. Examples of observation include watching a group discussion, laboratory experiments and music performances.

Interactions are when we are engaged with the student, asking them questions about their work or working with them as a collaborator. Interactions are always supervised assessments – the evaluator is engaged with the student. Examples are supervised projects, viva voces, class-based discussion and explanatory aspects of lab demonstrations. Interactions allow evaluators to better understand a student’s learning and get explanations of process (see Oral assessments guide). Importantly, they are also inherently moments of feedback to students, critical to learning. These moments can provide timely, meaningful feedback (Henderson et al., 2019). Every observation can move into interaction if the evaluator asks a question or directs an activity.

Three ways to control

Controls are the way we guide our students in their processes. Controls are influenced by the task set and evaluation methods used. All three control measures are enhanced or diminished by additional factors.

Supervision is the most direct control measure. Supervision here is a form of student control over observable processes. Thus the extent and quality of the supervision affects its ability to support the integrity of the assessment. Supervising an exam only controls the way students write answers; there is no supervision of their learning processes – and the extent to which they outsourced preparation to others (French et al., 2023). However, if the supervisor understands the task, it becomes possible to move from supervision to evaluation – through either observation or interaction. If the supervision is remote, additional issues arise.

Design: Well-designed assessments can strongly influence students to follow the processes intended and increase the likelihood of integrity (see here). As the evaluator is not present, no such measure can be entirely reliable, but they can make the effort of diverging from the process more trouble than it is worth to most students. There are many factors that can raise or lower integrity, and many have been affected by generative AI. Design is described in the assessment brief, and influences the nature of evaluation. Good design can incorporate elements of process into the assessment, though the assessment of that process may need to be via the proxy of an artefact.

Post-submission security is a final type of control measure that is extrinsic to the assessment task itself. These can be either human-based interactions or technology-based analysis.

Human-based measures involve either an evaluator drawing on previous knowledge of the student’s work to assess the integrity of what has been submitted (something that is often implicit in the way evaluators read artefacts), or interactively through viva voce-style conversations about either an artefact or a performance. Technology-based measures analyse artefacts using computer algorithms to indicate issues of inappropriate authorship or process. Any flagging by these systems needs a further analysis by an experienced educator to determine if any inappropriate behaviour has been identified. Effectiveness is linked to whether the measures act as deterrents, but the measures are likely to affect students differently (cf Piquero et al., 2011).

Creating harmony

Together these concepts build integrity in assessment. The task that the student is set influences the form of evaluation that is appropriate and the nature of the controls that can be applied. The utility of the controls can be increased by varying the nature of evaluation. Moving back and forth between the concepts and options chosen can help to better understand how to increase the integrity of assessment and improve our students’ learning.

Acknowledgments: this blog is based on discussions within the UNSW Assessment Assurance Working Group and a conversation with Dom McGrath, University of Queensland.

***

Reading this on a mobile? Scroll down to read more about the author.